Article written by James Crawshaw, Tillmann Lang and Prof. Dr. Falko Paetzold.

Finance is key to making our world a better place. Inyova, a digital impact investing company, enables investors to make use of it. By empowering investors to have a real impact. Backed up by the science of impact investing.

Every investment has an impact. Whether you know it or not, your money – even if it is only in your bank account – finances someone and something. From funding drilling expeditions in the Arctic to solar panel construction all the way to space travel, your money makes a difference: where the capital goes today determines how we will live tomorrow.

So, let’s have a look at the status quo.

What’s wrong with sustainable finance?

We live in a complicated world facing many issues. If investing our money can help to change it for the better, that’s a good thing—negative interest rates make storing savings in the bank account less appealing anyway, so why not invest in a ‘sustainable’ financial product? This is where many investors walk into a pitfall.

The problem for the responsible investor is made up of two things in particular:

- The lack of transparency. Often, it’s difficult to understand whether a particular investment is sustainable at all.

- The absence of impact. In the grand majority of cases, even sustainable investments will not change anything in the real world.

According to Morningstar, sustainable funds reached a new record high in the first quarter of 2021. In Europe alone, almost 3,500 funds are registered that label themselves as ‘sustainable’¹. The figures show a sharp rise in demand for sustainable investments: the appetite to do good is enormous among investors.

While the number of sustainable funds has multiplied in recent years, investors who choose to invest in a sustainable fund rarely know what they are actually investing in.

There are countless financial products claiming to be sustainable. Under the label of ‘ESG criteria’ (Environment, Social, Governance), funds invest billions in fossil fuel companies and corporations of dubious fame for their exploitative practices².

For a long time, there have been neither control bodies nor a uniform taxonomy describing what criteria a sustainable investment actually has to meet. As a consequence, greenwashing is widespread. Sadly, the trust that investors place in “sustainable” investment providers is not always justified.

Luckily, investment providers are becoming more and more stringent in applying sustainability in a senseful and rigorous way. But that doesn’t mean sustainable financing is doing anyone any good. Even if identifying “good companies” to invest in or successfully filtering out black sheep, these “sustainable” investments typically have no measurable positive impact on the environment or society.

Is sustainable finance failing us? A recent Greenpeace study³ concludes that sustainability funds have virtually no impact on climate and sustainability.

This raises the question: How can we get finance to have a positive impact?

Active ownership. The missing link in today’s capitalism.

The owners have left the room

Companies are owned by people. All of them⁴.

And what’s more, all of us are co-owners of most of the largest companies in the world—through the money in our pension systems, through the money invested through our life insurance contracts, and so forth.

In a capitalistic society, companies should do what’s best for their owners, right?

And if they don’t, can’t the owners make them do it?

Well, yes. In theory. The mechanism for owners to tell their companies what to do is shareholder voting. As an owner, you can vote on things like ‘what’s the company’s goal’, ‘what should it produce and how’, ‘who is the CEO’ and more⁷.

But: Most owners have left the room. They don’t vote.

One reason for this is the prevalence of funds and passive investing. Active and passive funds are very popular because of their ease of use and—sometimes—low cost. Investors can simply ‘buy in’ to the fund and let investment managers take care of their money.

This concept is very popular, as evidenced by the fact that the number of mutual funds doubled between 2007 and 2020⁵. The number of new ETFs is increasing even more – between 2003 and 2020 it has grown by a factor of more than 2,700%⁶ on a global scale.

And here’s the problem: People who invest in funds delegate their voting rights to the fund managers.

This delegation of responsibility has had a big effect. Whoever does show up to vote has a lot of power to influence a company’s path. The small group of owners that do vote has all the say. This is a major cause of problems like exaggerated focus on short-term shareholder value over long-term stakeholder value (think quarterly numbers rather than long-term growth), low corporate social performance and more⁷.

As a result, the interests of society at large—or even the interests of the people who actually own the company—receive little attention.

We are the owners. But we’ve left the room, leaving it to other people to decide for us.

Let’s take back control. By becoming active owners.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

We as owners can exercise our voting rights and become active owners through cooperation with other investors, through engagement, and by simply exercising voting rights⁸.

And this can mean big change!

Take the example of the nuns who started a shareholder initiative that forced an American arms producer to reason⁹. By systematically buying shares of the arms manufacturer Ruger over a period of two years, the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Oregon, USA, were able to hold the arms company accountable for its policies. Together with other investors, they managed to get Ruger to communicate more transparently about the dangers of weapons.

Sadly, doing all this is a LOT of work. It requires time, skill and knowledge. It’s difficult.

What if it was easy to be an active owner? What if shareholder engagement and shareholder voting were easy and fun things to do—rather than technocratic terms for a financial elite?

Luckily, action to ease things up is underway.

A great example is Engine No. 1, currently the only (!) ETF worldwide to actively exercise its voting rights and engage with the purpose of achieving positive change¹⁰. This ETF doesn’t give you the chance to exercise your own rights. But it ensures that the ownership rights are exercised in a responsible way, which is a BIG step forward.

Inyova is going a step further. Instead of giving you a responsible person to delegate your power to, we want to give YOU the power to be an active owner yourself. To do exactly that, empower everyone to create a better world through investing, is the reason why Inyova exists.

The science of sustainable investing and impact investing

“Impact investing” is often mentioned in the same breath as “ESG”, despite the fact that investments considering ESG aspects typically don’t have any actual impact¹¹.

In a recent paper, a group of leading sustainable finance scientists around Professor Timo Busch of the University of Hamburg presented a new typology of sustainable investments from an academic perspective. According to their findings, investments can be categorised contingent on their sustainability objectives and approach:

- Conventional investments

- Sustainable investments (ESG)¹²

- Impact investments

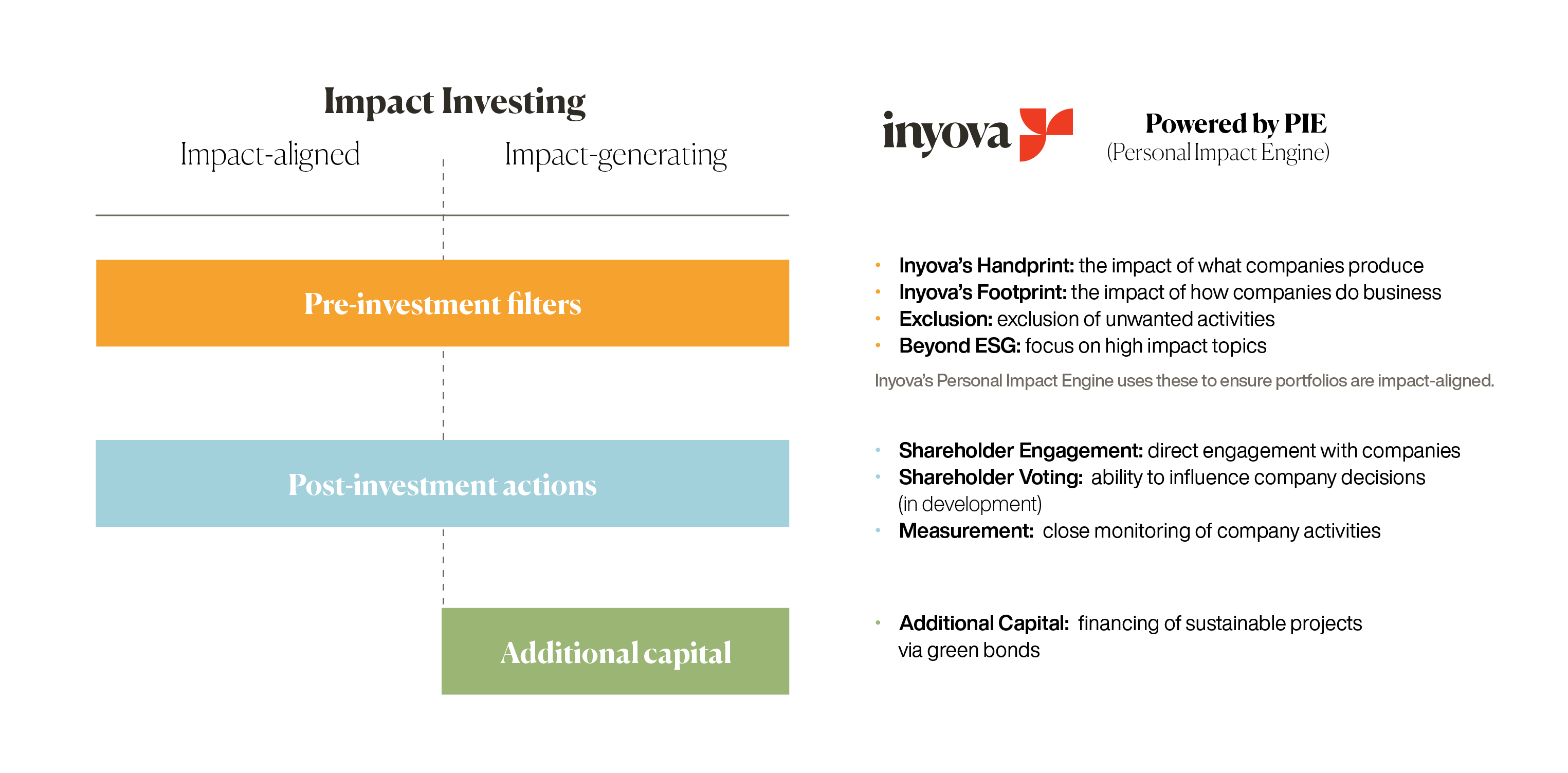

Exhibit 1: Differentiating conventional investing, ESG-related sustainable investing and impact investing

Conventional investments are designed to maximise return at minimal risk. Sustainability and impact are not considered.

ESG-related sustainable investments apply filter criteria to sort out which companies or projects to invest in and which ones to leave out. This happens before the investment takes place, which is why we call these filters pre-investment filters.

Typically, a certain variance of ESG criteria are applied to filter investable companies. One regularly used pre-investment filter is the exclusion of companies operating in certain industries. For instance, you can exclude weapon makers or tobacco firms. Another common approach is called best-in-class¹³. This approach selects the “best” companies within an industry. This means that you may simply invest in the “least bad” from a bad bunch.

It is worth noting that ESG pre-investment filters can be applied for financial reasons. (You don’t have to be a convinced do-gooder to buy into ESG investing.) ESG filters help avoid sustainability-related risks to an investment, such as emissions regulations harming profitability or stranded assets. After all, sustainability risks are financial risks.

A further important characteristic of ESG-related sustainable investments is that they hardly ever have an impact on the real world. An ESG investment may not make the world more sustainable in a measurable way. Despite this, ESG investments are an important step in aligning the financial industry with the real world, for instance by considering the risks stemming from climate change in long-term investment decisions.

Impact investments differ from ESG-related sustainable investments in that they are designed to have a measurable impact on the real world. While for an ESG investment it’s sufficient to consider what a company you invest in does (by applying pre-investment filters), for an impact investment it’s crucial that the investment changes how that company interacts with the world—in other words, that the investment itself has an impact on the real world.

Impact investments come in two shades. Impact-aligned investments address social and environmental challenges and goals. They take deliberate action to influence the companies they invest in for the better, for instance through active ownership. Such measures are called post-investment actions, because they take place after the cash has gone into the investment and remain relevant for as long as it stays there.

Impact-generating investments go even further. They bring money to companies, projects or ideas that otherwise couldn’t exist or grow. That’s what we call additional capital. Additional capital becomes available, for instance, when you provide money for a specific project, e.g. for reforestation, or for the development of a new decarbonisation technology. Other prominent examples are startup investments or microfinance.

Both impact-aligned and impact-generating investments consistently monitor and measure their impact.

Inyova’s approach to impact investing

Inyova was purpose-built to make impact investing possible for everyone. From the beginning, we have pushed boundaries to allow all people—and not just the big players—to make a difference.

How do we do it?

At the heart of Inyova is our technology: the Personal Impact Engine (PIE)¹⁴.

Through PIE, Inyova can create and manage personalised impact investing portfolios for our customers.

Inyova impact investing portfolios consist of 35 – 40 stocks, customised to your values and financial goals. Importantly, with Inyova you are the owner of your stocks and therefore a direct co-owner of the companies you invest in. Depending on your risk profile, your portfolio may also include bonds. Inyova offers its customers Climate Bond Initiative-certified green bonds.

Let’s take a closer look at how Inyova’s approach aligns with the science of impact investing. Exhibit 2 gives a high-level overview.

Pre-investment filters at Inyova

PIE applies pre-investment filters and portfolio theory to identify the companies best suited for your values and your financial situation. This happens by evaluating the handprint and footprint of each company in our investment universe. (Check out this whitepaper for details on how we do this.)

As a first step, all companies in our investment universe are thoroughly analysed and rated before we make them available to Inyova impact investors. With the Inyova handprint and footprint, which can both be selected by each investor individually, we have developed a model that captures the material impact a company and its products have on the world.

For the handprint, we consider what a company does, capturing the impact a company has through the products and services it puts out to the world. To ensure that the full impact of the product is taken into account, Inyova looks at the complete lifecycle of a product or service.

For the footprint, we look at how a company does business, capturing the impact of its operations. This examines factors such as a company’s level of CO2 emissions, how well it treats its employees, and how many women are in leadership positions.

After you have chosen your impact themes and excluded activities that do not match your values, our PIE impact engine selects companies on the basis of these scores and your personalised preferences. This prioritisation and selection of impactful companies ensures that your portfolio is impact-aligned.

Post-investment actions at Inyova

With regard to post-investment actions, Inyova holds shareholder engagement sessions with C-level representatives of the companies our investors are invested in. During these sessions, Inyova impact investors have the opportunity to ask critical questions, share their suggestions, and comment on the company’s progress with actual decision-makers.

In the future, even more direct shareholder engagement will be possible with Inyova. We are working on letting our customers engage directly with companies via a dedicated feedback system in our application.

We monitor the quantitative results of the companies our impact investors are invested in. And we do not hesitate to remove them from our investment universe if their actions do not align with our customers’ values. To do this, we monitor for controversies, and monitor their progress via specific ‘impact metrics’. This means that our investors are able to monitor how their companies perform in, for example, CO2 emissions as compared to global benchmarks.

We believe in shareholder voting as a key lever for impact. We are working on a unique voting mechanism, which will enable our investors to vote on issues concerning the companies they are invested in within the app.

Providing additional capital to sustainable projects

Inyova customers provide additional capital to sustainable projects through green bonds.

Green bonds are a well-established instrument specifically designed to raise money for climate and environmental projects. Importantly, the funds raised by green bonds are solely dedicated to financing green projects focussed on climate mitigation efforts—with independent auditors ensuring that this happens.

Via green bonds, Inyova impact investors are funding various green projects, from clean water in Chile to a wind farm in New Mexico. The green bond vehicle we use is entirely screened by the Climate Bond Initiative, which guarantees the sustainable character of the projects we finance via a strict use of proceeds (you can find more information on the Climate Bonds Standard here).

We’re taking back control

In order to fix the planet, we need to fix capitalism. Because we can only make change happen if we get the business community to rethink. To achieve this, we need to take action and become responsible, active shareholders who exercise their voting rights and engage according to their values. We must stop leaving funds and their proxies to do whatever they want and get closer to the companies we own. Let’s take responsibility for what our capital is doing. Inyova makes it easy. Join the mission. We’re taking back control.

Glossary

- Active ownership: Active ownership means actively exercising one’s rights as a shareholder. This includes, in particular, shareholder voting rights and engagement.

- Additional capital: Additional capital means providing firms or projects with money, which they can then use to enhance their operations, for example by funding the development of a new product or expanding into a new market. In the context of impact investing, providing additional capital refers specifically to providing firms or projects with the funds to generate a positive social or environmental impact.

- Best-in-class: Best-in-class means that, within a given sector or industry, a company is identified that best meets predefined criteria. With regard to ESG, a best-in-class approach could mean that oil companies would be compared to other oil companies and the ‘best’ (highest scorers on ESG indicators) of the ‘class’ (oil industry) would be selected for investment.

- ESG: ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and (corporate) Governance.

Environmental factors look at a company’s relationship with the environment, ranging from contribution to global warming to effects on biodiversity.

Social factors relate to how a company interacts with its employees and society, including factors like fair pay, diversity in their workforce, and community relations in the areas they operate in.

Governance factors look at how a company is run, including factors such as executive compensation, shareholder rights, and the overall decision-making structure. - ESG integration: ESG integration means that conventional investors systematically consider environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues in investment analysis, investment decisions and portfolio management. The reason for this is the conviction that the integration of ESG aspects helps to maximise returns by managing risks.

- Exclusion: Exclusion means cutting companies involved in certain industries out of your portfolio. Examples of frequently excluded areas include the alcohol, tobacco, and fossil fuel industries.

- Impact investing: Refers to investing in which impact on the world is strongly considered alongside financial return. Following Busch et al 2021, this can be split into two types of impact-related investments: 1.) impact-aligned and 2.) impact-generating.

- Impact investing – impact-aligned: Subcategory of impact investing. In order to meet the criteria of an impact-aligned investment, it is necessary to ensure that the companies selected are addressing social and environmental challenges and goals before and after the investment decision, e.g. by assessing contribution to the UN SDGs or by being better as compared to a CO2 benchmark.

- Impact investing – impact-generating: Subcategory of impact investing. Impact-generating investments actively contribute to social and environmental solutions by providing additional capital to green companies and projects. To do so, they exercise active ownership to prompt firms to change by effectively utilising voting and engagement in view of clear milestones. Importantly, it must be demonstrated that the investment has a significant effect on the outcome of the project.

- Investment universe: An investment universe is the pool of companies from which an investor can choose to invest. This generally involves the pool of companies having been screened subject to a set of rules, such as exclusion or impact-based criteria.

- Post-investment actions: Post-investment actions are measures taken by investors after they have already invested in a position. A classic example of a post-investment action is shareholder engagement, where investors engage in dialogue with the companies they are invested in.

- Pre-investment filters: A pre-investment filter is where a specific set of criteria is applied before the investment takes place. Selecting companies based on their material impact and excluding certain industries are two examples of pre-investment filters.

- Proxy voting: Proxy voting is when shareholders transfer their voting power to a representative. Usually, the shareholders tell their proxy what to vote on important company decisions at their annual general meeting.

- Shareholder engagement: This is where owners of company shares engage with management in order to bring about change in how the company operates. This can range from letters to meetings with high-level executives where shareholders lay out their wishes (e.g. more women in leadership positions, lower executive compensation, greener production processes). Shareholders are also often able to propose motions to be voted on at the next annual general meeting. For example, investors in a certain manufacturing company could propose a motion that obliges the company to reduce their emissions by a certain amount.

- Thematic investing: With thematic investing, investments are made in companies that are or will be the winners of a major structural trend. Such themes can be, among others, ‘subscription economy’, ‘new technology’ or the like. Thematic investing prefers to invest in trends that have an environmental, demographic, socio-economic and behavioural impact. The aim is to gain a financial advantage by investing in such “megatrends”. Sustainability thematic investments contribute to overcoming social or environmental issues by investing in companies offering solutions to these. Such themes can be ‘green energy’, ‘environmental change’ or similar.

Prof. Dr. Falko Paetzold is assistant professor in Social Finance at EBS University and also leads the Center for Sustainable Finance and Private Wealth (CSP) at the University of Zurich. CSP is a spin-off from the Next Gen Impact Investing programme that he co-initiated at the Initiative for Responsible Investment at Harvard University. Falko was a Fellow at Harvard, PostDoc at MIT Sloan, Sustainability Analyst at Bank Vontobel, and Partner at sustainable investing consultancy Contrast Capital. He founded GreenBuzz, the network of sustainability intra-preneurs. Falko holds a PhD from the University of Zurich and an MBA from the University of St. Gallen (HSG) in Switzerland.

Dr. Tillmann Lang is the co-founder and CEO of Inyova impact investing. For many years, Tillmann has been working on the question of how to make the world more sustainable – and the role finance has in this transition. Before founding Inyova, Tillmann worked for more than 6 years at the strategy consultancy McKinsey & Company. In addition, Tillmann was CFO of Benefiit, a network of impact investors, and is founding director of the Sustainability in Business Lab of ETH Zurich. He holds a PhD from ETH Zurich and studied mathematics and computer science at the universities of Heidelberg and Santiago de Chile.

James Crawshaw is Inyova’s resident Impact Economist, making sure Inyova is always at the forefront of impact research and incorporating it into our portfolios. He recently moved to Zurich from the UK after studying Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at the University of Oxford.

²For example, https://www.ishares.com/us/products/286007/ishares-esg-msci-usa-etf-fund has large stakes in the oil company Exxon Mobil and the fast food chain McDonalds.

³Greenpeace (21.06.2021). Sustainability Funds Hardly Direct Capital Towards Sustainability.

⁴Even if a company is owned by another organisation, it’s ultimately owned by people. For instance, state-owned companies ultimately belong to citizens.

⁵https://www.statista.com/statistics/278303/number-of-mutual-funds-worldwide/

⁶https://www.statista.com/statistics/278249/global-number-of-etfs/

⁷Desjardine, M. R., Durand, R. (2020). Disentangling the effects of hedge fund activism on firm financial and social performance. Strategic Management Journal, 41 (6), pp. 1054-1082.

⁸https://www.csp.uzh.ch/en/research/Academic-Research/Investor-Impact.html

¹⁰https://etf.engine1.com/

¹¹Busch, T., Bruce-Clark, P., Derwall, J., Eccles, R., Hebb, T., Hoepner, A., Klein, C., Krueger, P., Paetzold, F., Scholtens, B., Weber O. (2021). Impact investments: a call for (re)orientation. SN Bus Econ.

¹²Busch et al. distinguish between ESG-screened and ESG-managed investments. As our focus is on impact investing, we have simplified this and put them together in the category of ‘sustainable investments (ESG)’

¹³Best-in-class is a subclass of exclusion, as it excludes any company that is not best-in-class.

¹⁴The Inyova Personal Impact Engine (PIE) is what makes the fully personalised and transparent nature of Inyova portfolios possible. PIE is an automated algorithm that selects companies out of the Inyova investment universe depending on their impact, considering the companies’ handprint and footprint as well as your personal financial situation. (Read more about our investment approach in this whitepaper). After you have set your preferences, PIE will select stocks matching your profile and build you a fully diversified impact- and risk-optimised